#85. What I Learned from Gibson Biddle of Netflix [CEO Notes]

On Making Wicked Hard Decisions, Building World-Class Brands, and the 70% Rule

Dear Reader,

In June, I attended an exceptional product management event with Gibson Biddle, Netflix's former VP of Product, hosted at Monzo's London office. The session, titled "Wicked Hard Decisions," took us through 5 real Netflix cases that revealed how the streaming giant navigated its most challenging crossroads.

Drawing from his tenure at Netflix (2005-2010), where he helped lead the DVD-to-streaming transformation, Gibson shared frameworks that have become foundational to Netflix's $45 billion success.

As someone now navigating the complexities of running FC Urban across eight European cities, these lessons on decision-making under uncertainty couldn't have come at a better time. Throughout the session, I found myself drawing parallels between Netflix's challenges and our own—from building defensible community moats to making rapid expansion decisions with incomplete data.

This session held special significance for me. Three years ago, I wrote a 5-part series on The Streaming Wars, diving deep into how Netflix outmanoeuvred Blockbuster and evolved to face Disney. Hearing these stories from someone who was in the room when these decisions were made added extra context I wish I'd had when writing that analysis.

I thought it would be helpful to share my notes from the session, providing useful context for each case and links for further learning. Enjoy 😊

The DHM Framework

Gibson began with Netflix's core decision-making framework: Delight customers in Hard-to-copy, Margin-enhancing ways.

This framework forces you to find the intersection of three critical forces:

Delight: Creating genuine customer joy

Hard-to-copy: Building defensible moats

Margin-enhancing: Improving unit economics

The genius is in the tension. Anyone can delight by burning cash. The breakthrough happens when you find ways to delight that competitors can't replicate while improving margins.

Application for FC Urban: Our Masters (game hosts) who know players personally create delight, the relationships built over months are hard to copy, and the retention this drives enhances margins.

Here are the 5 cases.

The 5 Wicked Hard Decision Cases

Case 1: The 2005 Throttling Lawsuit - When Details Matter

Context: Netflix used a "Consumer Preference Score" to allocate new release DVDs, prioritizing active users. They failed to disclose this policy clearly.

Stakes: $5 million class action lawsuit

Decision Options:

Fight the lawsuit and defend the practice

Settle and change the policy

Decision: Settle

Gibson’s Lessons:

Details matter in customer communication

Distinguish between high and low stakes decisions

Eliminate or disclose any "yickiness" in your business model

“Yickiness” is the opposite of delighting users.

Case 2: The 2007 Blockbuster Battle - Strategic Patience

Context: Blockbuster launched "Total Access," allowing unlimited in-store DVD swaps for mail subscribers.

The Analysis:

Initial reaction: Lower prices to compete

Key question: "How long can Blockbuster sustain this based on DVD swap rates?"

Answer: 9 months

Decision Options:

Buy Redbox to compete on physical distribution

Lower prices to match Blockbuster's value proposition

Do nothing and focus on streaming

Decision: Do nothing on pricing. Double down on streaming.

Result: Blockbuster killed Total Access at exactly 9 months. Netflix had built an insurmountable streaming lead.

Gibson’s Lessons:

This inside view completely reframed my understanding of the Netflix vs. Blockbuster battle I'd analyzed—it wasn't just strategic brilliance, but disciplined decision-making with incomplete information.

Case 3: The 2007 TV Device - The $15M Write-Off

Context: Netflix built a TV streaming device (later became Roku) for $15M, one month from launch.

Stakes:

Only 10% of members streaming >15 min/month

High demand for TV-connected device

Investors/partners wary

$15M already spent

Investors/partners wary: Investors worried Netflix was losing focus by becoming a hardware company (competing with potential partners like Sony, Samsung), while content partners feared Netflix gaining too much control over the living room ecosystem. The device could transform Netflix from partner to competitor overnight.

Decision Options:

Launch the device

No launch

Decision: No launch

Gibson’s Lessons:

Sunk cost fallacy is real

Culture drives focus

Challenge plans even at the last minute

Urgent vs. important distinction matters

Patience to build platform > quick hardware wins

Case 4: Auto-Cancel Inactive Members - The $100M Ethics Test

Context: 0.5% of members hadn't used Netflix in 12 months but kept paying—$100M/year in pure profit.

The Question: Will auto-cancelling delight customers in hard-to-copy, margin-enhancing ways?

Decision Options:

Keep collecting the $100M annually (do nothing)

Auto-cancel with notification to save customers money

Decision: Launch auto-cancel with message: "To save you money, we're cancelling your membership—but you can restart anytime."

Gibson’s Lessons:

Case 5: The Qwikster Debacle

Note: Gibson referenced this as Netflix's biggest failure during the session but didn't detail it. I've reconstructed the case from his written analysis where he explores what went wrong.

Context: In 2011, riding high from successful hardware partnerships and a $100M bet on "House of Cards," Netflix decided to split its DVD and streaming services into two separate brands: Netflix (streaming) and Qwikster (DVDs).

Decision Options:

Keep DVD and streaming bundled as one service

Separate into two distinct services with different brands

Decision: Launch Qwikster as a separate DVD service, requiring customers to manage two accounts with a price increase.

Result/Stakes:

800,000 subscribers lost in Q3 2011

Stock crashed from $300 to $65

Customer outrage forced reversal after just 3 weeks

Reed Hastings admitted "I messed up," apologizing for lacking "respect and humility"

Lessons:

Success breeds dangerous overconfidence

Customer obsession must override strategic elegance

Even with great frameworks, you'll fail sometimes—recognize it quickly and reverse course

Stay humble, especially after big wins

Gibson's hypothesis: Qwikster failed because Netflix stopped obsessing over customers. The DHM framework would have caught this—splitting services was neither delightful nor margin-enhancing for users.

The 70% Rule

One of Gibson's most practical frameworks: You need 70% of the data to make a good decision. Less is reckless. More is procrastination.

This aligns with Jeff Bezos' concept of "Type 1 and Type 2 decisions"—most decisions are reversible (Type 2) and should be made quickly with 70% information.

Reed Hastings reportedly told Reid Hoffman: "A world-class management team gets it right 70% of the time. If you're right more than that, you're not taking enough risk."

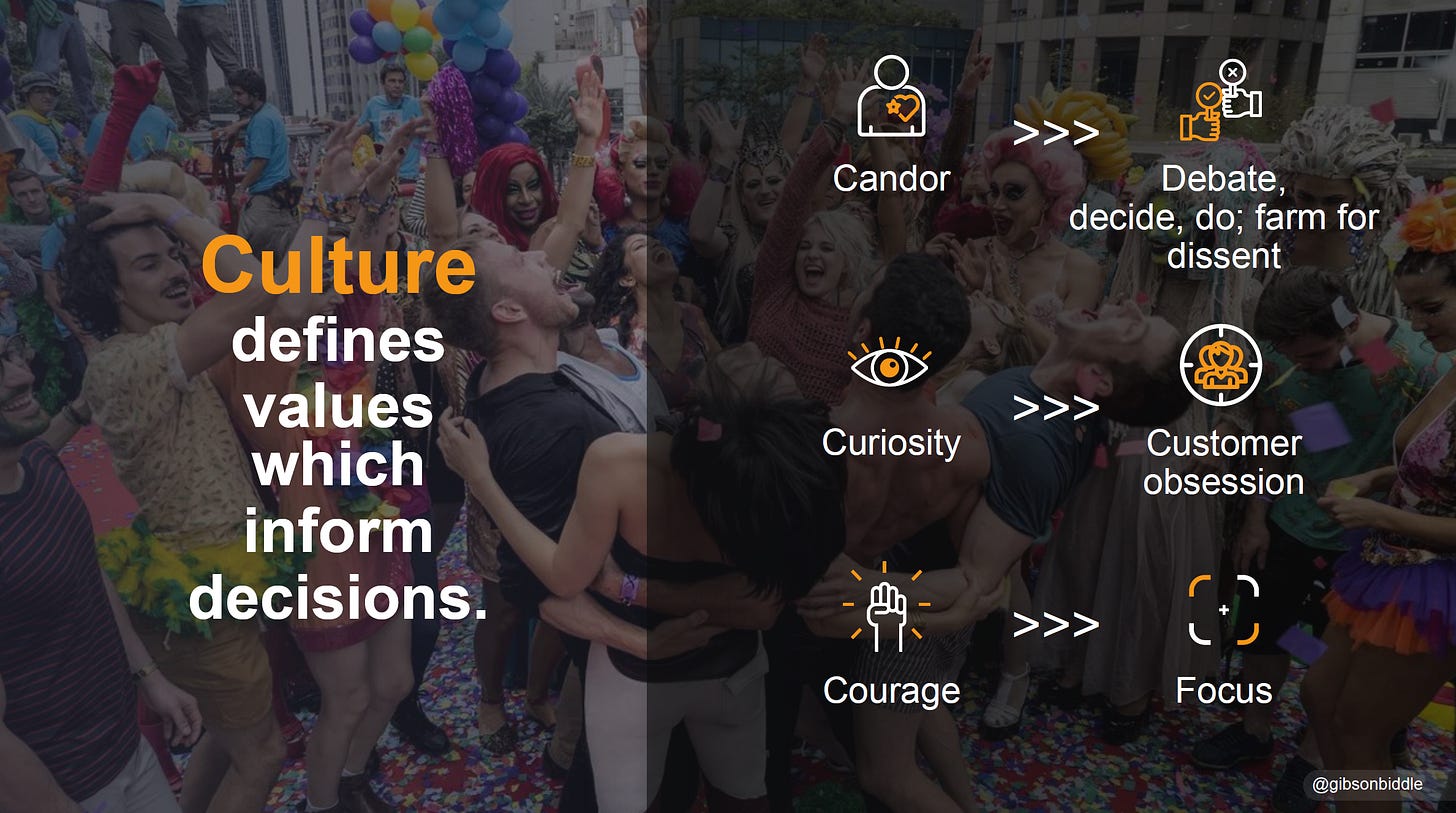

Culture as Decision-Making Operating System

Netflix's culture wasn't just values on a wall—it was how they made decisions:

During Monday executive meetings, Reed Hastings would force participants to flip positions mid-argument—ensuring not just debate, but genuine understanding of all perspectives.

This reminded me of Ben Horowitz's "What You Do Is Who You Are"—culture is what you do when facing hard decisions, not what you say in meetings.

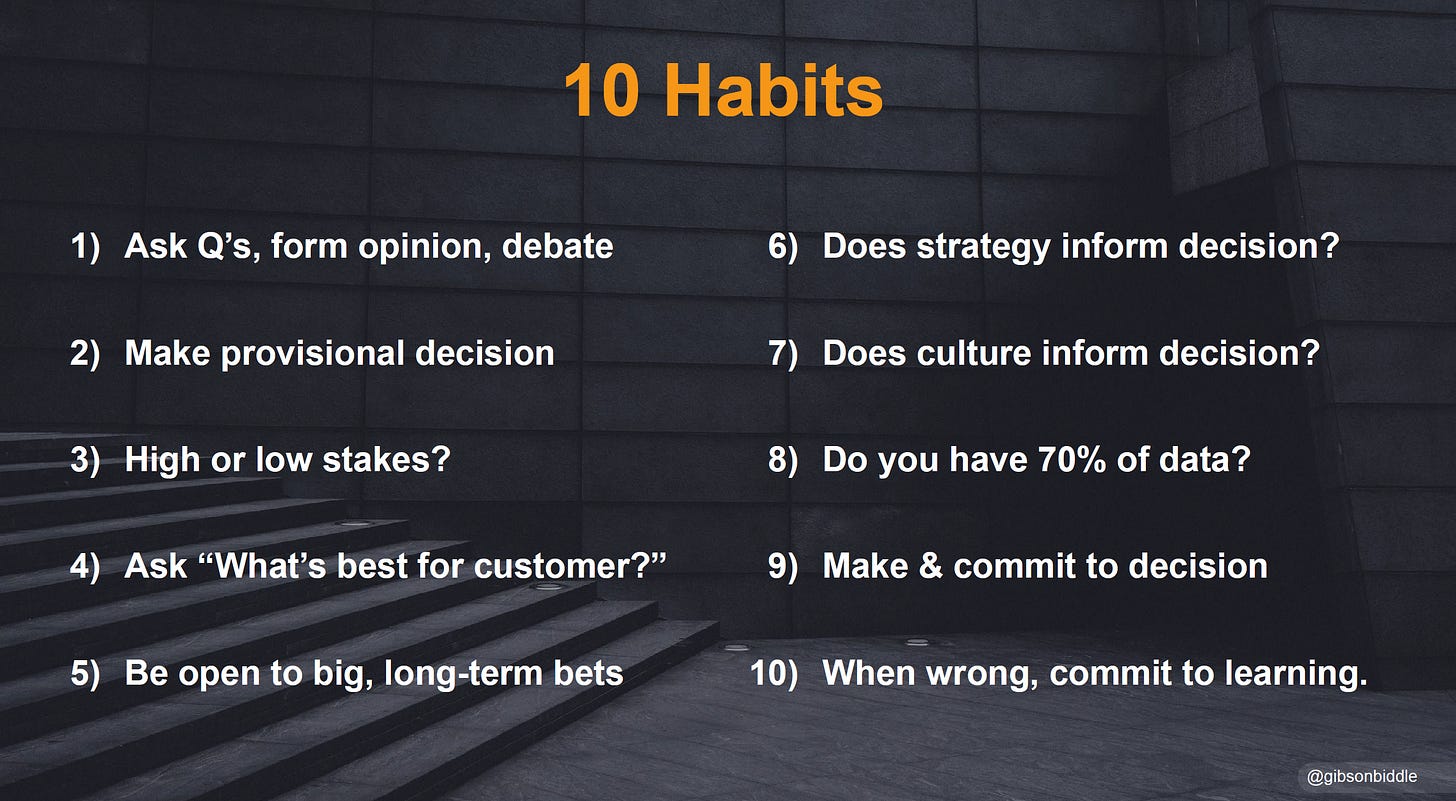

The 10 Habits for Making Wicked Hard Decisions

Gibson closed with his decision-making framework and 10 Habits we can build for making wicked hard decisions:

Ask questions, form opinion, debate - Farm for dissent, force position switches

Make provisional decision - "Based on what I know, I'd do X. What data would change my mind?"

Determine high or low stakes - Magnitude? Reversible?

Ask "What's best for customer?" - Can you represent their voice?

Be open to big, long-term bets - How does strategy inform this?

Does product strategy inform decision? - DHM framework application

Does culture inform decision? - Which values apply?

Do you have 70% of data? - If yes, "decide & go"

Make & commit to decision - No second-guessing

When wrong, commit to learning - Capture insights, apply to next decision

Key Insights from the Q&A

On aligning three forces: It takes time to align strategy (plan), culture (operating system), and consumer science (experiments). The magic happens when all three inform your decisions.

On consumer science: Netflix used four data sources—qualitative research, surveys, empirical data, and A/B testing. This ensures customers are represented in key decisions.

On provisional decision-making: Make a decision with current data, then identify what additional information could change it.

Additional Resources from Gibson

Gibson has written extensively about these concepts:

Application to FC Urban

In my current role as CEO at FC Urban, I am applying 3 immediate implementations from this session:

Adopting the DHM framework for all product decisions. Every new feature must delight players, be hard for competitors to copy, and improve our unit economics.

Implementing the 70% rule to increase decision velocity.

Creating a "decision journal" to document why we made each choice, then reviewing quarterly to improve our process.

The shift from product manager to CEO demands faster decisions with broader impact. These frameworks provide the structure to move quickly while remaining focused.

Key Takeaways for Product Leaders

On Risk: A world-class team gets decisions right 70% of the time. More than that means you're not taking enough risks.

On Focus: Every decision should align with your strategy. If it doesn't help you delight customers in hard-to-copy, margin-enhancing ways, it's a no.

On Learning: Learning is more important than being right. Document why you made each decision and review quarterly.

On Speed: Most decisions are low stakes and reversible. Move quickly on these. Save deliberation for the truly high-stakes choices.

Closing Thoughts

This session reinforced something I've been exploring in my transition from PM to CEO: great decision-making isn't about having all the answers—it's about having the right framework for finding them.

Netflix succeeded not because they always made right decisions (remember Qwikster?), but because they had a systematic approach to making data-informed decisions when the path was unclear.

Gibson's frameworks complement what I explored in my piece on Grand Strategy—navigating ambiguity through balancing opposites and developing judgment. Where that article focused on the philosophical approach to decision-making (being both fox and hedgehog, balancing theory with experience), Gibson provides the tactical tools—the 70% rule, the DHM framework, the 10 habits. Together, they form a complete approach: strategic thinking meets operational execution.

As Gibson noted, decision-making can be learned. It's not the domain of "strategic geniuses" but a practiced art that improves with the right frameworks and deliberate practice.

The meta-skill isn't knowing the answer. It's having a framework for finding it, the courage to act on incomplete information, and the humility to learn when you are wrong.

Many thanks to Gibson Biddle for sharing these insights and to the Monzo team for hosting this excellent event.

Until next time.

Nero

The Best is Yet to Come

Did you enjoy this event review? Check out my previous sessions with Shreyas Doshi on Finding Your Superpower and Issra Omer on Building Products at Spotify.

You can subscribe now to receive all my articles including deep dives and career articles, technology and product articles, business breakdowns, and book reviews.